Read through the slides and then arrange the objects in desending order.

Artificers were craftsman, who made (artifices) items that required a particular, specialist skill. The example shown here is a glover, a potentially lucrative trade that could help its practitioner rise in society.

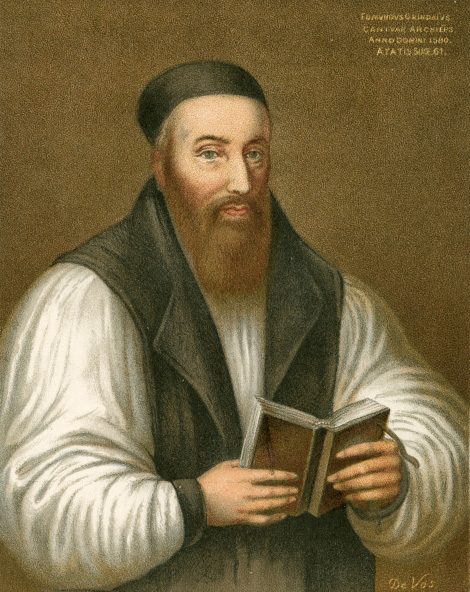

Bishops were the Lords of the church and were appointed by the Queen to oversee its governance. They also sat in the House of Lords and had in the past usually formed part of the monarch’s Privy Council, though few were appointed to that group by Elizabeth. Edmund Grindal, shown here, never joined the Privy Council although he rose to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

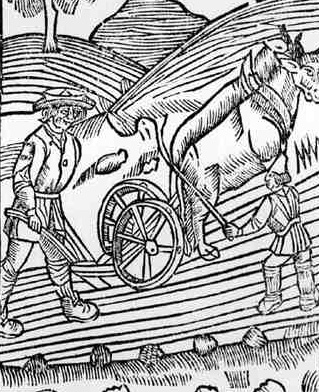

Farmers played a vital role in the Elizabethan economy. Some owned their own land but others worked as tenant farmers. There was a wide range of agricultural activities, from sheep farming to arable, growing crops to produce food.

Lawyers were members of the legal profession and played extremely prominent roles in government during Elizabeth’s reign. Nicholas Bacon is shown here clutching a roll of parchment, indicating the scholarly and educational attributes of his profession. He was knighted on Elizabeth’s accession in 1558, indicating the complexity of arranging differing individuals within the larger category of the ‘gentry’.

The titled nobility comprised a small group of men – just 57 at the start of Elizabeth’s reign. Nobility could either be inherited or estowed by the monarch. Most noblemen still felt themselves to have a primarily military identity, along with the duty to serve the monarch as advisors. Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex claimed both and is shown here after a successful military expedition against Spain in 1596.

To be a yeoman could indicate one of two things: either that the individual was an attendant in royal service, as represented in the image here, where yeomen are included in Elizabeth I’s funeral procession. Alternatively, a yeoman could be a farmer of relatively superior status, owning his own land and usually cultivating it himself.

Knights, addressed as ‘Sir’, followed by their first name, were like noblemen in that their title retained a military significance, although by the time of Elizabeth’s reign many men were given knighthoods for service in government or other fields of endeavour. Sir Philip Sidney, shown here wearing partial armour, was killed fighting in the Netherlands in 1586.

A burgess was a resident of a town, often with an added dimension during the Elizabethan period of being a ‘citizen’, actively involved in local government. The image here shows the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of the City of London, who held particular privileges of autonomous government.

Labourers, then as now, worked in a manual capacity for low wages. The Elizabethan economy could not have functioned without them.

Another title with military origins, an esquire was a man who had the right to ‘bear arms’, in effect to display his family’s gentility through the use of heraldic devices deriving from the families from whom he and his wife were descended. This is something that John Shakespeare secured in 1596. We can see the family coat of arms displayed here above his son William’s tomb in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Education was highly valued in Elizabethan society and scholars were respected for their learning and often maintained close friendships with members of the elite. John Dee was a mathematician, astrologer and antiquary who occasionally advised the Queen and was connected to other leading figures at her court.